From Space to Surf: Satellites Confirm the Power Behind December’s Monster Swells at Waimea and Maverick’s

Satellite data from ESA’s Climate Change Initiative and the French–US SWOT mission have revealed the true scale of December 2024’s extreme storm energy, the same system that sent XXL surf to Waimea Bay for The Eddie and detonated Maverick’s the next day. What satellites measured from orbit, surfers felt on the reef: a two-day pulse that redrew both science charts and big-wave history.

What happened and when

- 2024 December 22 — Eddie Aikau at Waimea Bay: event confirmed and widely covered; Landon McNamara declared the winner (World Surf League coverage).

- 2024 December 23 — Maverick’s session: Alo Slebir rode a massive, widely shared wave at Maverick’s. The wave has been reported at 76 feet in some outlets, though that measurement is disputed by observers and analysts.

Video & first-hand footage

Watch: MASSIVE WAIMEA BAY | 2024 EDDIE AIKAU

Watch: Alo Slebir — Maverick’s, December 23, 2024

The numbers — claimed, contested, and the world record

- Some outlets reported a 76-foot measurement for Slebir’s Maverick’s wave. That figure has been circulated widely in social and video captions but faces scrutiny from independent measurers and observers.

- The current Guinness World Record for the largest wave surfed is Sebastian Steudtner’s 86-foot ride at Nazaré on 29 October 2020 — an officially certified benchmark for comparison.

Why caution is needed: measuring wave height from photos and video is fraught: camera angles, lens compression, tow positions and lack of standardized ground truth make single-source estimates unreliable. That’s why the surf community often debates large-wave claims until multiple independent measurements align.

Satellite tools and the measurement conversation

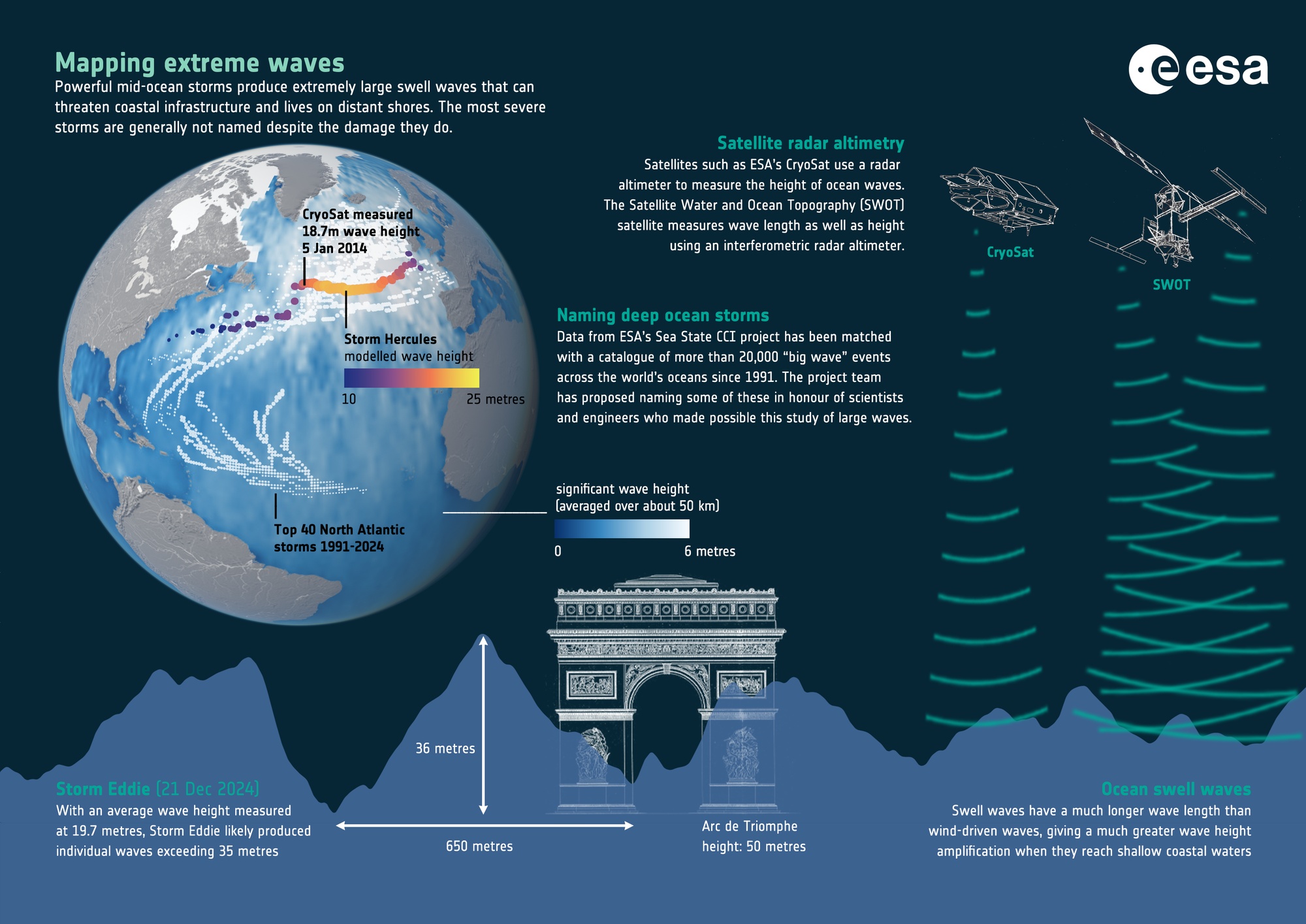

New satellite tools are changing the conversation about extreme waves. The SWOT (Surface Water and Ocean Topography) mission — a NASA/CNES project launched in December 2022 with ESA participation — provides novel, wide-area measurements of sea-surface features that researchers are now applying to storm-wave analysis.

A number of analyses circulating in the science and media sphere have used early satellite-derived estimates to describe very large storm waves (some reports cite average storm-wave heights around 19.7 m and peak values above 35 m). These satellite-derived numbers are promising for contextualizing extreme events, but they still require careful peer-reviewed validation and cross-checks with in-situ data and established measurement methods before being treated as definitive.

Experts in oceanography including researchers such as Dr. Fabrice Ardhuin, who works on ocean wave dynamics and remote sensing, provide important context when satellite estimates are discussed. Their work helps explain how satellite footprints, temporal sampling and algorithms can bias or refine height estimates.

➡️ Read the full ESA study: Satellites reveal the power of ocean swell (ESA, Oct 2025)

The surf take: what this means for riders and fans

– For riders: these were not waves to casually test limits. Heavy swell, shifting currents and local bathymetry make Waimea and Maverick’s unforgiving. If you’re not in a rescue-ready crew with experienced jet-ski pilots and water patrol, you don’t go.

– For event organizers and water-safety teams: satellite data and rapid video analysis offer new tools for post-session verification and for building more robust safety protocols around forecasted extremes.

– For fans and content creators: judge big-wave claims cautiously. A sensational frame or a dramatic edit can easily overstate raw size.

Open questions and the controversy to watch

– Measurement dispute: The 76-foot claim for Slebir’s wave is notable and should be treated as provisional until independent, documented measurements are published.

– Satellite validation: early SWOT-based figures are headline-grabbing, but the community should wait for peer-reviewed confirmations from ESA/NASA or academic journals to fold those numbers into the official record.

Bottom line

December’s late-season storm gave big-wave surf two headline moments: a contest held and won at Waimea, and a Maverick’s candidate for one of the year’s biggest rides. Both matters are now part of the conversation about how we measure, verify and celebrate extreme surfing — and both underscore that claims about size belong to the community until science, sober measurement and independent verification agree.